by Joe | Jul 29, 2005 | Articles

John LeKay: Music is obviously in your blood I don’t think that playing the violin the way you do is something that can be easily taught or learned. I know that you were born in St. Petersburg Russia and that both your parents were classical musicians. What instruments did they play and what kind of influence did this have on you taking up the violin and how old were you when you first began playing?

Joe Deninzon: My parents are both classical musicians. My father is a violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra, and my mother is a concert pianist, so I started out with music in the womb and in the house as I was growing up. My parents are also busy teachers, so there would be constantly multiple violin and piano lessons going on in the house. I was originally classically trained on the violin, starting at age 6. We emigrated to the states from Russia when I was 4. At around age 8 or 9, I started watching MTV and was seduced by the sights and sounds of Van Halen, Michael Jackson, yes, and just about everything in the pop mainstream that was floating around in the mid eighties.

Joe Deninzon: My parents are both classical musicians. My father is a violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra, and my mother is a concert pianist, so I started out with music in the womb and in the house as I was growing up. My parents are also busy teachers, so there would be constantly multiple violin and piano lessons going on in the house. I was originally classically trained on the violin, starting at age 6. We emigrated to the states from Russia when I was 4. At around age 8 or 9, I started watching MTV and was seduced by the sights and sounds of Van Halen, Michael Jackson, yes, and just about everything in the pop mainstream that was floating around in the mid eighties.

I wanted to be a rock star and started rebelling against my parent’s strictly classical teachings. This lead to my later taking up bass, guitar, and writing and singing my own songs. The first instrument I learned to improvise on was the electric bass when I joined my high school jazz band at age 15. My heroes, growing up, were Led Zeppelin, Kiss, Aerosmith, Jaco Pastorius, John Mclaughlin, and Miles Davis. During these years, I still kept on with my classical violin studies, but it was a separate world from my jazz and rock dabblings.

Two pivotal things happened that led to me becoming a jazz/rock violinist. When I was 16, a local Cleveland songwriter with a string of minor hits, named Michael Stanley, invited me to perform with his band on the violin. I had never improvised on the violin before, but I knew the language from playing bass and guitar. The audience responded very well to what I was doing, and I realized that I could really stand out if I kept developing my jazz violin chops. Later that year, my father bought me a Grappelli/Django recording, which completely changed my life and opened my ears to all the possibilities.

As far as phrasing, I think I was more influenced by guitarists than violinists. Some of my favorite players of all time are Django Reinhardt, Jimmi Hendrix, John McLaughlin, John Scofield, Pat Metheny, and Steve Vai. I guess you could say I’m a guitarist trapped in a violinist’s body.

JL: In reference to the two pivotal things that led you to becoming a jazz/rock violinist and composer; how did it feel taking the leap from the world of classical violin to the world of improvisational jazz and rock? Also can you please describe what it is about Django’s guitar playing in particular, that has had such an impact on your music?

JD: I think what inspires me the most about Django’s playing, besides the immense virtuosity, is the Gypsy spirit and unique phrasing he brought to the music. Although Jazz is rooted in the history of Black America, anyone in the world who becomes a jazz musician brings their own heritage into it, thereby enriching the Jazz tradition. I think Django was one of the first to bring a European flavor to jazz. His phrasing was very unique for its time, and his style is such that it spawned a whole school of guitar playing that continues to this day. There is a distinct French-ness to compositions such as “Nuage”. I respect Django because he did not try to imitate the great jazz musicians from America, ( although I’m sure he was influenced by them), but put his stamp on the music. He was proud of where he came from and who he was. My roots being in Russia, I am a big fan of Gypsy music from Eastern Europe, and I can relate to the way Django plays, and probably have adopted some of his phrasing into my playing.

The transition to becoming an improvising violinist for me was relatively easy, because I had been playing guitar and electric bass for 4 years prior to my first improvisational violin experience. I had a basic knowledge of jazz, blues, and rock language. It was just a matter of finding the fingerings on the violin to execute the lines I was hearing in my head. Learning improvisation is very different from studying classical music. When practicing a concerto, you are dealing mainly with phrasing and articulation, and mastery of difficult passages. Once you memorize the piece and bring it to a good performance-ready level, you know you can move on to the next project. When you practice improvised music, you are theoretically analyzing everything you play. There is, initially, a lot of brainwork involved. A great deal of ear training and understanding of harmony. also, it is open-ended. you are never “finished” working on a piece because there are infinite things you can do with everything you work on. Also, a concept or lick you learn could surface in your playing months or years after the time that you practice it. I think one uses a different part of their brain when practicing jazz vs classical.

JL: I find it amazing that Django could not read or write and could not take musical notation and had to rely on someone do this for him. Also that he never played the same piece, the same way twice. When you said there are infinite things you can do with everything you work on, are you also this way in terms of approaching your own work and playing the same piece in different ways. Also do you use a particular method of taking notation or recording, during the early composition and creative stages, especially in terms of harmonic conception and the spontaneous development of melodic and rhythmic ideas and solos etc.?

JD: In answer to your question. I have different ways of writing. Sometimes a whole song will come to me in a flash, and I’ll write it down as if it was always there. Usually, I get these flashes at random moments. In the middle of the night, in the shower, when I’m jogging, etc.

The rest of the time, especially lately, I get bits of melodies that stick in my mind. So I keep a journal of licks and phrases. Sometimes I’m working on a composition and I have a space I need to fill, so I’ll look through my “riff diary” and find something that works, or that I can slightly alter to work in the given situation. Sometimes, a riff can lie around for years before I find a way to apply it to something.

Once the main structure of the song is created, it takes on a life of its own as my band performs it over time. Once the song has really gotten under our skins, we feel free to change the arrangement or the groove on a whim.

I never feel like a song is “finished”. To me, it’s a living breathing thing that is constantly changing, so I understand why Django could never play a song the same way twice. I can relate to that.

Unlike Django, I’m a very notation-oriented guy. I write everything down. This is good because I can compose while flying on a plane or in the back of a taxicab. Like Django, many great artists, especially in the world of rock, from Jimi Hendrix to Paul McCartney, never learned to read or write music. It is not a necessity, but I think it gives you more freedom if you know how. I heard that Michael Brecker could not read music until he was 18.

JL: What’s the musical landscape like out there in terms of playing classical music and how is the highly advanced studio recording technology and computers changing the way music is being recorded and released? Also can you tell me some of the musical tips you use to teach your students?

JD: In today’s musical landscape, string players have to be more versatile than ever to survive. Orchestral positions are few and far between, and increasingly hard to land, and many orchestras are folding or giving their musicians pay cuts. Meanwhile, conservatories continue to crank out many excellent classical players. The competition is fierce, and many people who spent their whole life focusing on classical music and not exploring other avenues, find themselves switching careers when they are not able to make a living doing what they trained to do. In many cases, musicians are not aware of all the opportunities that exist outside of the classical world. Therefore, I think it is crucial for any string player (or any musician for that matter), to study improvisation in many styles as well as composition. Even though I was classically trained on the violin, and studied jazz for many years, I find that a small percentage of my work is strictly classical music or traditional jazz. I have played with and arranged for many pop and rock singer songwriters and bands, blues groups, fusion bands, DJ’s, Italian, Brazilian, and Sephardic world music ensembles. Even though every style of music requires a different approach and different language, the skills I learned initially were a doorway to all of these styles.

With my students, I usually divide the time equally between classical and non-classical styles. We spend a great deal of time working on classical technique and repertoire, which I feel is the foundation for everything else. The second half of the lesson is usually spent working on a variety of things dealing with improvisation. The first thing I teach is the blues, which is the cradle of most popular music in the 20th century and beyond. We learn about jazz theory and harmony, learn as many standards as we can. I also try to educate them on techniques for playing rock and working with effects. I try to encourage my students to write their own songs and give them as much advice as I can. It’s fun to to re-create for my students some of the experiences that brought me where I am today.

I think there is a growing movement in improvisational education for strings in this country. More colleges are offering jazz string programs, and Mark O’Conner’s Fiddle Camp has become a Mecca for string players who want to expand their horizons.

As for your question about technology, I think the growing development of Protools, Logic, and all the home recording technology is putting a great deal of power and creativity into the hands of musicians and putting big studios and record labels out of business. It is much easier to produce and manufacture a good sounding CD at home and distribute it on the internet. You can act as your own producer, engineer, radio promoter, publicist, etc. There are also thousands of mechanisms that can alter the sound of your instrument. Midi has enabled a violin to sound like a flute or a french horn. All the effects that I like to use can allow you to paint with more colors than ever. I think the challenge is to use the technology in a tasteful and musical way and not as a gimmick or novelty. That is a journey that every musician has to make. It’s a personal decision as to what you want technology to do for you and to what extent you want to use it.

JL: Can you tell me about your band Stratospheerius and the most recent pieces you have been working on? Also what plans do you and your band have for the future?

JD: Stratospheerius is my vehicle to explore the endless scope of sounds that a violin can create, especially when put through a variety of effects. I have always been fascinated by sounds and textures, and am a proud fan of fusion music, especially that which was created in the early seventies by the likes of Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Frank Zappa, and Jean Luc Ponty. Jean Luc, who was highly influenced by Grappelli, was probably the most important jazz violinist of his generation. He and Jerry Goodman were two of the early players to use distortion, wah, and delay on the violin. There is an art and a skill to tastefully playing with effects and not using them as a gimmick. When one listens to guitarists from Jimi Hendrix to John McLaughlin, Steve Vai to Dave Fiuczynski, and most recently Oz Noy, one realizes that guitar players and as well as keyboard players have made leaps and bounds in effectively applying sound effects to music in the last 30 years. String players are still behind in this technique, in my opinion, and there are plenty of things to explore. Stratospheerius is a 4-piece band consisting of bass, drums, guitar, and myself on vocals and 4, 6, and 7-string electric violin. Our music is a mixture of funk, jazz, worldbeat, and jam-rock. Heavily influenced by the artists I mentioned above, as well as pop groups like Dave Matthews and Sting.

Having released a very successful live CD that has been getting heavy airplay, we are currently preparing to record a new studio album (which will be our fourth), and continue touring.

In addition to this, I have 70% of an acoustic album recorded, which will probably include the version of Nuage that you heard. This is a complete departure from Stratospheerius, and consists of an acoustic violin, upright bass, and guitar. Nothing was plugged in or overdubbed. I hope to have it out sometime next year.

by Joe | Jun 29, 2005 | Articles

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

By Dave Richards

JOE DENINZON WAS BEYOND PLEASED WHEN RANDY HETHERINGTON SECRETLY RECORDED DENINZON’S WHOLE ERIE SHOW LAST YEAR

JOE DENINZON WAS BEYOND PLEASED WHEN RANDY HETHERINGTON SECRETLY RECORDED DENINZON’S WHOLE ERIE SHOW LAST YEAR

He was caught in the act, live. But instead of feeling violated, Joe Deninzon was elated. He never sounded so good.

When Deninzon and his band Stratospheerius played at Forward Hall in April 2003, he was unaware that sound engineer Randy Hetherington recorded the entire show from his Oz-like enclave behind the stage.

“I was so in the moment, I hadn’t noticed he put mics around the amps and drums and spontaneously recorded the set,” Deninzon said in a phone interview. “When we were done, he led me to his secret laboratory behind the stage, where the big studio is, and started playing us the show. I was like,’Wow! This is killing me.”

Deninzon was so pleased with how his jazzy jam-funk band tore it up that night he decided to release it. All but two of “Live Wires” sizzling tracks were recorded at Forward Hall. The artist believes it turned out better because he was unaware he was being recorded.

“The best stuff, I’ve found, comes when you’re completely not self-conscious and letting inspiration fly,” he said. “He captured a moment, which was one of our best shows.”

Others agreed. With “Live Wires,” Deninzon beat out hundreds of acts to wqin the best-jamband category in the fourth Independent Music Awards in January. Judges included Delbert McClinton, Erukah Badu, Victor Wooten, and Loudon Wainright.

“What’s That Thang,” the soaring, supercharged lead-off track, is included on the compilation CD, drawn from 2004 IMA winners.

DENINZON PLAYS ELECTRIC violin, not exactly your standard jam-band instrument. But he wails on it as wildly, furiously, intensely as Hendrix attacked his guitar. He studied classical music as a youth, and still loves it. In fact, his wife, Yulia Ziskel, is first violinist witht eh New York Philharmonic.

“When I teach my students, I encourage them to keep up with classical studies, even if they want to be rock violin players.That’s the foundation of everything,” Deninzon said. “But I was also drawn to rock and roll at an early age and fell in love with it. I felt it was a great way to communicate with people and felt it was something I could do well and I felt free doing it. As much as I enjoy classical, I feel there’s a limitation on how you can express yourself in that medium.

His love for jazz and classical shine through on “Live Wires.” So does a sense of playfulness, evidenced by Stratospheerius interpreting-ahem-Danny Elfman’s theme song from “The Simpsons.”

Doh!

“It’s a fun thing,” Deninzon said. ‘A lot of people love it, and radio picked it up even more than the other stuff. It’s a song that everyonbe knows. A lot of rock bands cover his music. He’s a great composer.

Deninzon includes that “The Simsons” theme on “Live Wires,” which has put his career into overdrive. It’s earned airplay across the country as well as overseas in Italy, Russia, and other countries. His CD also made the top 20 list for XM Radio’s “Jazz and Beyond.” Chick Corea took the No. 1 spot.

“It’s been a really good year,” Deninzon said. “We found out about the IMA award in January, and we’ve gotten heavy radio promotion all around the country. We’ve gotten into a lot of good festivals over the summer.”

Last Saturday, he played at the massive Riverbend Festival in Chattanooga, Tenn, which also featured Big & Rich, Trace Adkins, Pat Benatar, and others. But he’s happy to return to the scene of the crime-Forward Hall-on Friday.

“I hope it has the same spontaneous, wild feel that we had for the live one,” he said. “I’m excited about the new music we’re putting together, and we’ll be performing some of it in Erie. So we’ll see what happens.”

by Joe | Nov 29, 2004 | Articles

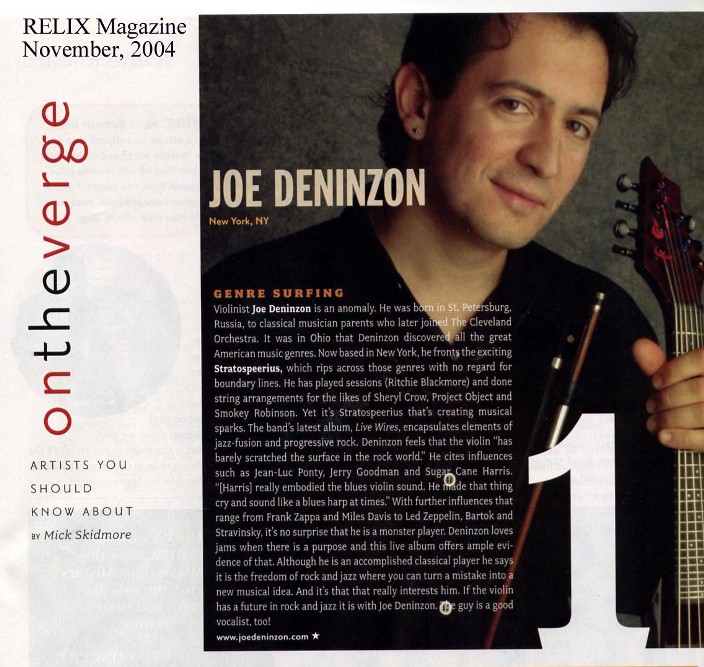

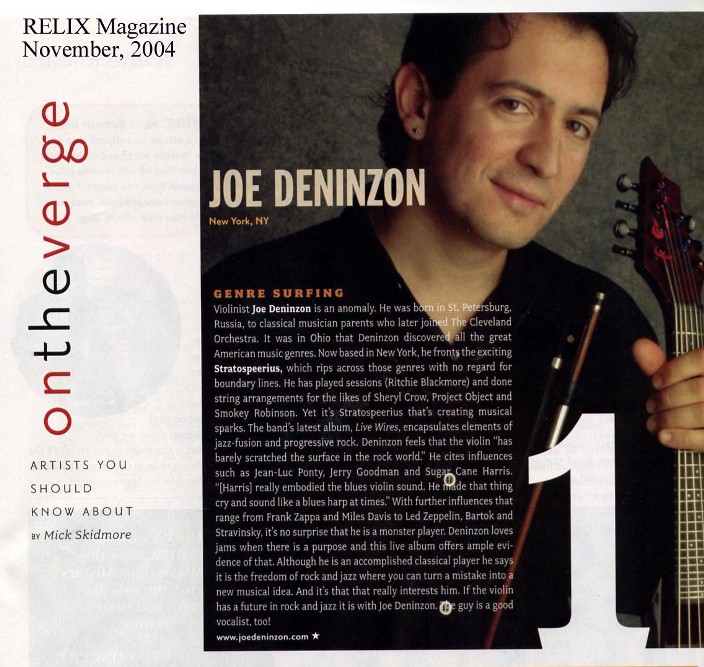

Violinist Joe Deninzon is an anomaly. He was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, to classical musician parents who later joined the Cleveland Orchestra. It was in Ohio that Deninzon discovered all the great American music genres…

by Joe | Oct 20, 2004 | Articles

Joe Deninzon Wants to Take You Higher

by Jedd Beaudoin

If you’ve not yet listened to one of Joe Deninzon’s amazing albums, whether his studio work on Electric/Blue, Adventures of Stratospheeriusor his current Live Wires, then you need to run – not walk – to some portal on the Internet, buy them and immerse yourself in this Russian-born violinists magic. Or so says SoT’s Jedd Beaudoin who sat down for a phone interview with Deninzon last summer. Read on to learn more about this very talented musician.

SoT: Why’d you decide to a live record at this point in time?

Joe Deninzon: It started with Dave Koerner , a guy I knew for years in Cleveland. I would see him at every concert that I’d go to, especially prog or jazz fusion shows. He’s one of those obsessive bootleggers. I think he’s bootlegged more shows that he’ll have time to listen to in his lifetime. At one point I had a gig out there and he was taping my show and I invited him to travel with us and do sound and merchandise. He would tape all of our shows. So, after about two years I’d accumulated all these bootlegs. I started going through them and found some really good stuff, some of which had been multi-tracked. In addition to that, we’d done a show at a place in Erie, PA called Forward Hall, opening for a band called Freakbass. After our set this guy came up to me and told me that he’d recorded our show, then showed me this secret studio that was behind the club, this huge facility, and it was awesome. And the best thing was that we didn’t know that we were being recorded, which is great because you’re not self-conscious. You don’t care and that’s when you get the good stuff. So, between that and the bootlegs, we had a wealth of material to choose from. So I thought that we had to get that stuff out.

SoT: There’s material from your studio records on there but there’s new material as well. Was it important to you that this record wasn’t just a rehash of the studio records?

JD: Well, a song like ãAcid Rabbits,ä which I first recorded in Î97 or Î98 has changed so much since then because we’ve played it live a lot over the years. Now I wish that I could have thought of those ideas back then when I wrote the song and recorded it. It’s almost a different song now, so I thought it would be a unique opportunity to bring it across the way that I’m hearing it now. As for the new stuff …. A lot of my favorite Zappa CDs, the live stuff, consist of all-new material that he’d never recorded in the studio. We had a lot of new songs that we’d been playing, I thought the versions were cool, so I thought it would give people something new right along with the new versions of older material.

SoT: I wanted to ask specifically about “Heavy Shtettle,” which you co-wrote with Alex Skolnick. I think that that’s a great example of the diverse styles that you’re capable of working in.

JD: I guess it came from playing with a lot of world music groups over the years in New York. I’ve played with a lot of Middle Eastern groups. I was in a band with Alex’s ex-wife Ofri Eliaz. I was introduced to that music through that band. Having played it so much I started hearing it in my head and started writing down little licks that sounded Middle Eastern. When I got together with Alex, he came up with the bridge and it sort of celebrates our Jewish roots and our heavy metal roots as well. [Laughs.]

SoT: Did you have an affinity for Middle Eastern music before that?

JD: I think that I was always influenced by gypsy music. As a classical violinist, I played pieces such as “Zigeunerweisen” by Pablo de Sarasate, a great gypsy violinist and Brahms’ Hungarian Dances some of that, that old schmaltzy, Jewish kind of sound. But also, I’ve been checking out guys like Simon Shaheen, who’s a great oud and violin player from [Tarishiha, Galilee], who’s played with Sting and a bunch of different [people] …. But being around people who play the oud and so on, that’s opened up all kinds of different horizons for me. So, I’ve been working different kinds of ethnic music into my own and, also, it’s part of my heritage, so I celebrate that as well as my love of rock ‘n’ roll and progressive music.

The title of that piece actually came because Alex said that someone had been joking with him about forming a band called Heavy Shtettle. [Laughs.] I thought, “Hey, that’s a cool name.”

SoT: On this new record, you’ve done your version of the theme from The Simpsons. On Adventures of Stratospheerius you did a version of ãPeppermint Patty .ä There are probably some who are wondering just how big of a cartoon fanatic you are.

JD: That was a really spontaneous thing. We were working with this guitarist named Jake Ezra, who plays on most of this CD. He’s a really excellent guitar player. He’s a huge Simpsons fanatic. I mean, I love the Simpsons but not like this guy. But, one rehearsal, he started noodling, playing the Simpsons theme and I started playing that lick, then it turned into a jam and I said, ãHey, we should do this. People know this and they love it and Danny Elfman wrote it. He’s such a baddass, just a great composer. So, it just sort of naturally evolved. It wasn’t one of those things where I consciously sat down and wrote an arrangement.

SoT: Well, it also lends this whimsical quality to the record, which is refreshing.

JD: A lot of people take themselves too seriously, especially in the prog and fusion world. I’m all about having fun. I think that it invites more people to listen to music, if they hear something that they like with a little twist. You should have fun and keep what you’re doing entertaining for yourself and your audience.

SoT: You also perform a version of Frank Zappa’s “Magic Fingers.” Was that inspired by your tenure in Project/Object or does it go deeper than that?

JD: I first heard the song, I think, when I saw 200 Motels when I was maybe 16. I loved it and I became a huge Zappa fan. Project/Object covered that song a lot and it became one of my favorite songs of all time. I thought that it was one of those forgotten songs that could have been a classic but never really got on the radio. I like uncovering songs like that and letting people hear them. That’s also the idea behind doing [Stevie Wonder’s] “Contusion.” That’s a melody that I’ve loved and a lot of people that I know love but was never a “hit.” It’s fun to cover songs like that.

SoT Your solos sound great on this record. Are you happy with where you’re at as a soloist?

JD: I don’t think that I’m ever happy. I don’t think that any musician ever is. I’m always trying to develop and grow and explore new territory and improve my soloing and every aspect of what I do. But I am happy with the way that the CD came out, I am happy with the band played. But it’s an ongoing process. Until you reach your dying day, I guess. [Laughs.]

I look at guys like John McLaughlin, someone who’s covered so many musical worlds in his lifetime and he’s in his 60s now. He’s still going. It’s a lifelong journey. As soon as you say, “This is it, I’m a genius, I can’t possibly learn anything new,” that’s when you’re in trouble.

SoT: Is you interest in world and ethnic music part of that?

JD: Absolutely. There’s a lot of music that I’d like to study more in-depth. I think that I’ve only skimmed the surface of world music. I really want to study Middle Eastern music more deeply, as well as Brazilian music as well as country fiddle music. I’m a huge fan of Mark O’ Connor. We had the pleasure of opening for him a few years ago and that’s a whole world that’s sort of foreign to me because I didn’t grow up around it. I didn’t grow up around bluegrass and fiddle music. There’s just a lot of things that I’d like to explore. There are endless possibilities that you can explore as a musician. And all of these things influence my writing in the fusion realm as well.

SoT: Like O’Connor, you also play guitar. What is it about both of those instruments that appeals to you?

JD: I always tell my students to study another instrument. I say, “Don’t study with me, study with somebody else.” [Laughs.] I always tell people that I benefited from having played bass for a number of years. I learned about really locking into a groove and harmony and I benefited from guitar because I learned Jimi Hendrix, McLaughlin and Steve Vai licks and I also compose on guitar, so all of those things [are exactly] what I bring to the violin. And, of course, finger-style technique, pizzicato on the violin …. There are some connections and it’s fun to try and play your instrument outside of the clichés of your instrument. It’s always great to try and imitate a voice, a horn, guitar, that’s where the real creativity begins, I think.

SoT: You’re also a music educator as an outsider in that world, I have a sense that younger people are picking up the violin, viola, cello, etc. Is that your experience? Do you think that maybe it’s OK these days to play these instruments rather than just reaching for a guitar?

JD: I think that younger people have always played stringed instruments but that maybe in the last 20 years … you know, you can’t be a rock star and play the violin. There’s a lot of ignorance there. Maybe it’s bands like the Dave Matthews Band and Dixie Chicks and so on … a lot of bands use violinists now. It’s sexy, it looks cool and I think that maybe a lot of kids are getting turned on to to the instrument. And there are guys like Mark Wood who go around to schools and talk about the violin. I actually bought one of his 7-string, flying V, Viper violins with frets. People see that or they see a violin with a rap band and they see that there’s more to the violin than stuffy classical music, though classical music is great. But I think that in order to get kids interested, you have to show them all the possibilities. I know a lot of really good players who are getting more involved with education. I think that the next generation’s going to blow us all away. [Laughs.]

by Joe | Apr 29, 2003 | Articles

Walking in the considerable footsteps of Rock fiddle greats like Jean-Luc Ponty, Deninzon has composed some of the most inspired fusion jams since the heyday of The Dixie Dregs and Chick Corea…

by Joe | Aug 29, 2002 | Articles

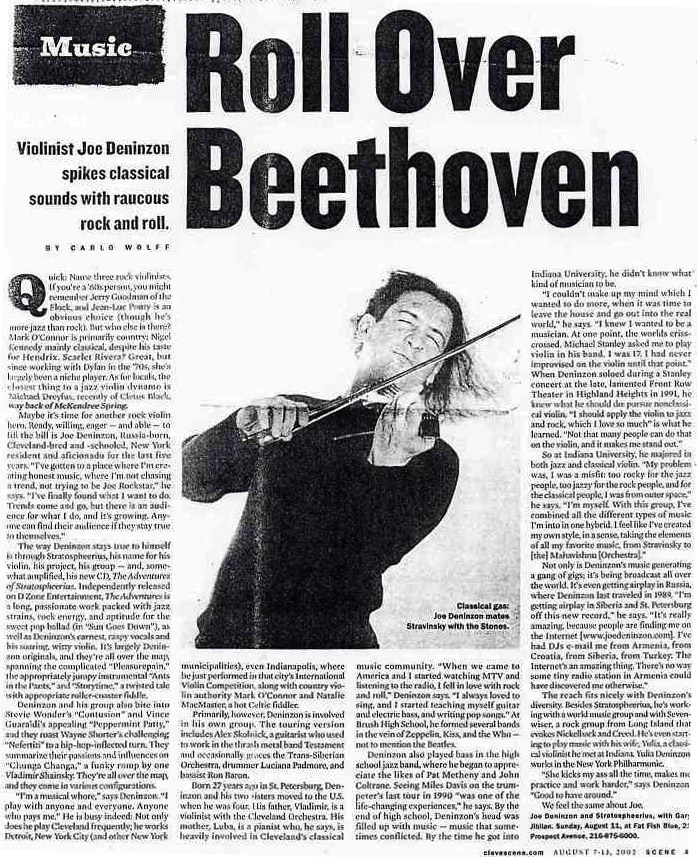

Roll Over Beethoven: Violinist Joe Deninzon spikes classical sounds with raucous rock and roll. Quick: Name three rock violinists. If you’re a ’60s person, you might remember Jerry Goodman of the Flock, and Jean-Luc Ponty is an obvious choice (though he’s more jazz than rock). But who else is there?

Joe Deninzon: My parents are both classical musicians. My father is a violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra, and my mother is a concert pianist, so I started out with music in the womb and in the house as I was growing up. My parents are also busy teachers, so there would be constantly multiple violin and piano lessons going on in the house. I was originally classically trained on the violin, starting at age 6. We emigrated to the states from Russia when I was 4. At around age 8 or 9, I started watching MTV and was seduced by the sights and sounds of Van Halen, Michael Jackson, yes, and just about everything in the pop mainstream that was floating around in the mid eighties.

Joe Deninzon: My parents are both classical musicians. My father is a violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra, and my mother is a concert pianist, so I started out with music in the womb and in the house as I was growing up. My parents are also busy teachers, so there would be constantly multiple violin and piano lessons going on in the house. I was originally classically trained on the violin, starting at age 6. We emigrated to the states from Russia when I was 4. At around age 8 or 9, I started watching MTV and was seduced by the sights and sounds of Van Halen, Michael Jackson, yes, and just about everything in the pop mainstream that was floating around in the mid eighties.

JOE DENINZON WAS BEYOND PLEASED WHEN RANDY HETHERINGTON SECRETLY RECORDED DENINZON’S WHOLE ERIE SHOW LAST YEAR

JOE DENINZON WAS BEYOND PLEASED WHEN RANDY HETHERINGTON SECRETLY RECORDED DENINZON’S WHOLE ERIE SHOW LAST YEAR